You don’t need different press attacks for different presses. One comprehensive strategy based on simple, time-tested principles does the trick.

Defeating full-court pressure begins with understanding the nature of pressing defenses, then adopting an aggressive attack strategy that will seize the initiative from the defense. In this series of five blogs, I’ll outline a comprehensive approach to defeat full-court pressure. Here are the first three lessons.

Lesson 1: It’s an insult to be pressed.

When confronting full-court pressure, far too many teams seem content to cross the ten-second line instead of attacking the basket. Maybe it’s a lack of confidence or a perceived shortage of ball handlers. Whatever the reason, you don’t get points by merely crossing half-court.

Generally, this kind of approach invites greater pressure and indecision, culminating in one or more catastrophic breakdowns as the game proceeds.

Beating full-court pressure starts with believing it’s an insult to be pressed, and consequently, a willingness to accept pressure in the backcourt so that you gain an advantage in the frontcourt. Your goal is to punish the press by scoring points against it.

Lesson 2: All presses are the same.

You don’t need different press attacks for different presses. Once the ball is inbounded, all presses are the same.

Before the throw-in they may look different—man-to-man, various zone traps, even presses that combine man and zone principles—but in reality, they’re all the same. Or more accurately, they can be attacked in such a way as to render them the same.

The key is learning the underlying attack principles by practicing live, five-on-five, every day of the season. That’s what creates the confidence and the skill to attack full-court pressure and score points against it.

Lesson 3: Spread the floor.

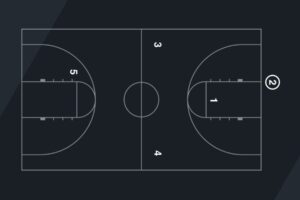

The court is 94 feet by 50 feet. That’s 4,700 square feet. Make your opponent defend the entire area by aligning your players across the width and length of the floor.

Don’t congest the backcourt by bringing five attackers forward. Instead, spread them out. Here are two examples of useful attack formations.