This article was written by By Stephen Shea, Ph.D. You can find out more about Dr. Shea and his work in the field of Basketball Anayltics below the article.

Editor’s Note I don’t believe that this data is the only factor in determining what are and aren’t good shots in your system, but it is something to consider. It is also something to consider looking at on an individual basis for the players that take most of your shots.

On August 2, 2014, @ShaneBattier tweeted, “Kids, bottom line. Don’t take dribble jumpers unless your last name is Nowitzki. Thank me later.”

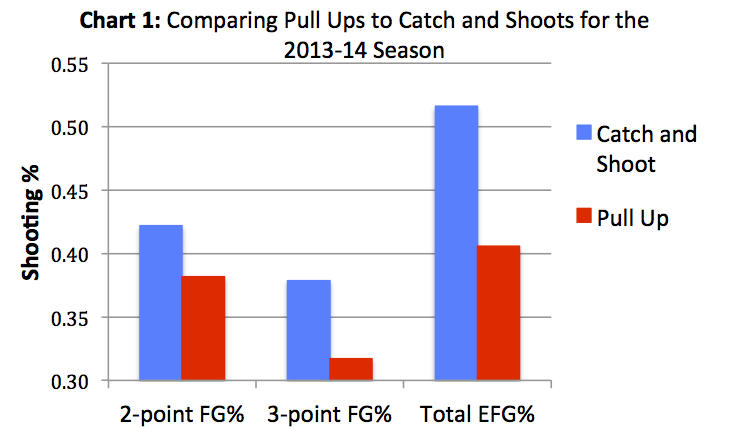

SportVU’s new spatial tracking statistics on NBA.com split jump shots by whether or not the shooter dribbled before the attempt. If the shooter dribbled, the shot is a pull up jump shot. Otherwise, it is called a catch and shoot. Chart 1 below shows the FG% and EFG% for pull ups and catch and shoots for the 2013-14 regular season. It appears that Battier was correct. Individual anomalies (like Dirk) aside, pull up shots are quite inefficient in comparison to catch and shoot jump shots.

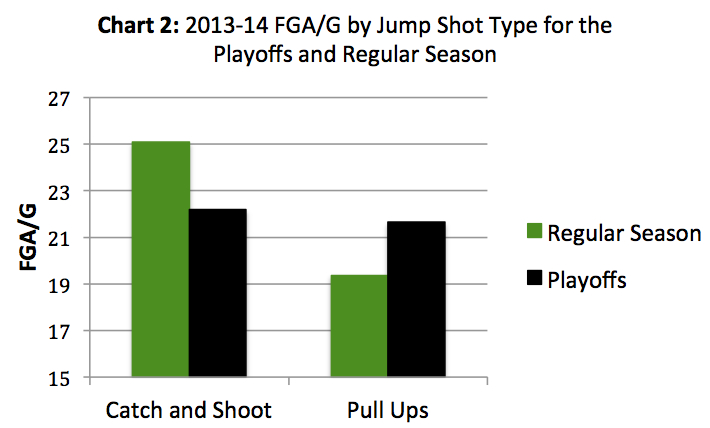

Not all minutes are equal in their importance for a team. When a team is up 20 in the fourth quarter, it is unlikely that they will call their best plays or play their best players. In contrast, playoff basketball is dense with meaningful minutes. Partly due to the increased defensive intensity, teams up the number of pull ups relative to catch and shoots when the playoffs come around. See Chart 2. (Note that for Chart 2, we only used the 16 playoff teams in the calculation of regular season numbers.)

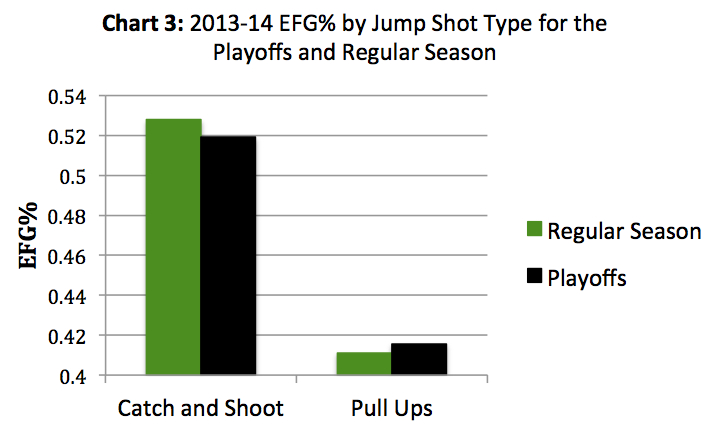

In the playoffs, teams take more pull ups, but these field goal attempts are still the far inferior shot. Chart 3 displays the EFG% for each shot type in the 2013-14 regular season and playoffs. (Again, regular season means only the regular season production of the 16 teams that made the playoffs.)

Charts 1 and 3 show that jump shots off the dribble are significantly less efficient than jump shots off the pass. However, it is too simple to conclude that players need to stop taking dribble jump shots.

Players do not have equal opportunities to take high quality catch and shoot jumpers. Yes, certain players are better at moving without the ball and putting themselves in position to catch and shoot. Yes, other players tend to force dribble jumpers with plenty of time on the shot clock or when a teammate is in position to take a better shot. Still, there are differences in opportunities.

Game situation and quality of teammates are contributing variables. Players can be forced into dribble jumpers after a play breaks down and the shot clock is running out. A player may benefit from more open looks on the perimeter because his teammate (such as LeBron) draws double teams. Simply put, the specific percentage of shots a player gets off the pass in comparison to off the dribble is partly a reflection of the activity of the team around him.

On November 19, 2014, a match between the NBA champion Spurs and LeBron’s new Cleveland crew went down to the wire. With 26 seconds on the clock and 15 seconds on the shot clock, Manu Ginobili stood out by half-court as the Spurs held a 1-point lead. It was a pivotal possession—the type of possession where we would expect to see a star work in isolation. This is the type of situation where Durant, LeBron or Carmelo might be given the ball in isolation and asked to work their magic. Often, the star would dribble a few times make a move and try beat the opponent on the drive or step back to a jumper. In either case, it would be a shot off the dribble. The Spurs—the consummate team—showed that there are other (perhaps easier) ways to finish a game.

Ginobili passed to Parker with 22 seconds on the clock. Ginobili then moved to the block as Parker passed to Duncan (after no dribbles and with 20 seconds on the clock). Ginobili faked like he was going to break to the perimeter. His defender (rookie Joe Harris) bit, and Duncan dumped the ball to Ginobili for an uncontested layup with 19 seconds left on the clock. Three passes in 3 seconds and Ginobili had an easy bucket. Ginobili did not have to break down a defender and dribble to the hoop. The great passing of the Spurs negated the need for moves with the ball. It was a reminder of how experience, chemistry and passing ability can trump one-on-one skills. The Spurs won the game 92-90.

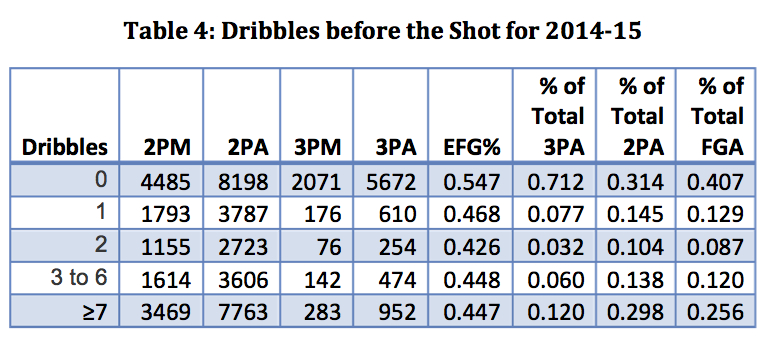

This season, NBA.com has added new sections to their stats pages. Now, each team and player has dashboards. One of these is a shots dashboard. Among the new statistics on this page is dribbles before the shot (as captured by SportVU). Here, all shots are included (not just jump shots). So, the Ginobili layup would register as a shot with no dribbles. Table 4 presents the league total splits of 2 and 3-pointers by number of dribbles for 2014-15 (prior to the games on Friday, November 21). The table also splits EFG% by number of dribbles. Shots after no dribbles tend to be more efficient.

The new dashboards on NBA.com provide another level of detail on player shot types. Unfortunately, they are still not optimally split for certain types of analysis. For example, it would be nice to see these numbers split by whether or not the shot occurred in transition.

Although not presented with an ideal level of detail, these new dashboard statistics are still interesting and provide information that was not previously available.

Our data on pull ups vs. catch and shoots shows that jump shots off the pass are far preferable to jump shots off the dribble. Table 4 shows that this relationship persists when we include more than just jump shots. But players and teams cannot simply wake up one day and decide to only take shots off the pass. The play described above involved three players that are in their 13th season of playing together. That type of ball movement, which was executed perfectly at a crucial moment in the game, comes with maturity and experience. Or does it?

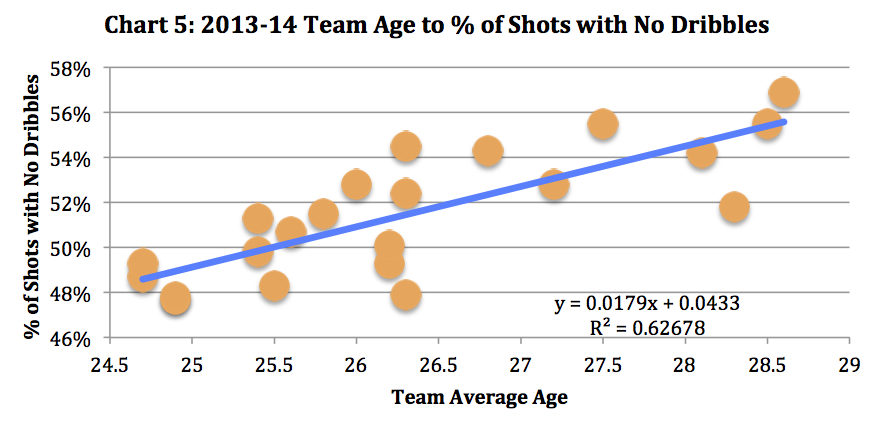

I went back and compared a team’s average age in the 2013-14 season to their % of FGA on no dribbles. Ideally, one should weight the average age by playing time as many very good teams carry older veterans at the end of the bench and rebuilding squads fill those spots with young players that are more parts potential than production. Instead, I’ll take the lazy way out and just exclude the 4 youngest and 4 oldest teams. This had the added benefit of removing the Nets who added significant pieces in Garnett and Pierce in the offseason, had a first year coach and lost center Brook Lopez early in the season. All of these could hinder the team’s ability to execute seamlessly on offense (at least early in the season). At the younger end of the spectrum, we removed Philadelphia, a team that is …well…ummmm….planning for the future?

Chart 5 displays a surprisingly high correlation for this simple study. It certainly appears as though players learn how to better set up teammates and players learn to look less for shots off the dribble as the team matures.

About the Author, Stephen Shea

Stephen Shea is an associate professor of mathematics at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, NH. He earned a Ph.D. in mathematics from Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT, and a B.A. in mathematics from The College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, MA. His mathematical expertise and publication record is in the areas of probability, statistics, dynamical systems, and combinatorics. For years, he has been applying his abilities in these areas to study professional and amateur sports. Stephen is a managing partner of Advanced Metrics, LLC, a consulting company that provides analytics solutions to basketball and hockey organizations. At Saint Anselm College, he runs a course on sports analytics. His sport writing has been featured in the Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports, Psych Journal, the Expert Series at WinthropIntelligence.com, and the Stat Geek Idol Competition for TeamRankings.com. In 2013, Stephen coauthored the book, Basketball Analytics: Objective and Efficient Strategies for Understanding How Teams Win, and co-created the accompanying blog BasketballAnalyticsBook.com. In 2014, he authored Basketball Analytics: Spatial Tracking.