Humility is not Optional. It’s a Necessity

Cory Dobbs, Ed.D. The Academy for Sport Leadership

“Humility is not thinking less of yourself, it’s thinking of yourself less.” –C.S. Lewis

As we descend deeper into a society characterized by polarization and division, cooperation is increasingly a curious characteristic. First, let me suggest that cooperation is a product of humility, a dispositional drive of a selfless ego. I introduce cooperation here to set it up as a desired individual behavior to be exercised in a team environment.

Consider humility to be a serious personality characteristic; one that is geared toward the positive construction and building of healthy relationships. But don’t align humility with meekness or shyness—as is usually the case. Resist the temptation to dismiss humility simply because it hasn’t been lionized like “grit,” or “mental toughness.”

One of the biggest mistakes coaches make is thinking that humility means a lack of self-confidence or a personal shortcoming such as a fragile sense of one’s self.

In team relationships humility shows through by the team members’ commitment to serve and support one another, through showing appreciation for the contributions of teammates, expressing encouragement, and acceptance of each other. The person possessing a healthy dose of humility is generous with his or her support of others as expressed through loyalty and respect for teammates.

The humble teammate displays a strong sense of duty to the team. Let me be clear: humility is the social glue that holds the team—a fragile eco-system—in balance. Humility always contributes to unity.

It is worth exploring how to mesh cooperation with competition. Competition—a cherished quality in the field of sport—is often considered to be the opposite of cooperation. Competition is the drive and compulsion to win, to earn, to get, to have, to do. Sports and competition are synonymous. Yet, an ego attuned to only competition breeds a self-interested ego. At this point I’m sure you’re saying…”and so?”

We live in a culture with a high tolerance for individualism. This breeds status and ego. It promotes selfishness (might I get creative and say “selfieness”), and an “It’s all about me” attitude. Society rewards those who use self-promotion to stand-out. Of course, many young people have bought into this approach to life. However, there is often a darker side to ego. Ryan Holiday, author of Ego is the Enemy, reveals:

“The ego we see most commonly goes by a more casual definition: an unhealthy belief in our own importance. Arrogance. Self-centered ambition….The need to be better than, more than, recognized for, far past any reasonable utility—that’s ego. It’s the sense of superiority and certainty that exceeds the bounds of confidence and talent.”

An ego out of control can and often does promote a sense of self-justification giving an individual the “freedom” to say and do whatever is in their best interest. Ego driven people often are self-absorbed and seek only individual fulfillment. Certainly such behavior can and often is displayed on the playing field.

However, don’t confuse this with a default proposition that competitiveness is bad; it’s clearly not. But when an ego (triggered by a social or psychological event) is out of touch with reality it can quickly put a person on a path to self-destruction. And when this happens good luck reaching the person; you likely won’t until they meet with a fall that humbles them. Reality meets humility.

A humble person, one driven by a strong and stable sense of humility, is simply more likely to help a teammate, to regard others as equals and worthy of a deep, close relationship. Simply said, the humble person who practices humility keeps their accomplishments, gifts, and talents in a proper perspective. They possess self-awareness, avoid self-serving distortions, and are keenly aware of their limitations. They value the welfare of teammates and have the ability to mindfully attend to the uniqueness of each team member. Humility always contributes to unity.

About Cory Dobbs, Ed.D.

Cory Dobbs is the founder of The Academy for Sport Leadership and a nationally recognized thought leader in the areas of leadership and team building. Cory is an accomplished researcher of human experience. Cory engages in naturalistic inquiry seeking in-depth understanding of social phenomena within their natural setting.

A former basketball coach, Cory’s coaching background includes experience at the NCAA DII, NJCAA, and high school levels of competition. After a decade of research and development Cory unleashed the groundbreaking Teamwork Intelligence program for student-athletics. Teamwork Intelligence illuminates the process of designing an elite team by using the 20 principles and concepts along with the 8 roles of a team player he’s uncovered while performing research.

Cory has worked with professional athletes, collegiate athletic programs, and high schools teaching leadership and team building as a part of the sports experience and education process. As a consultant and trainer Dr. Dobbs has worked with Fortune 500 organizations such as American Express, Honeywell, and Avnet, as well as medium and small businesses. Dr. Dobbs taught leadership and organizational change at Northern Arizona University, Ohio University, and Grand Canyon University.

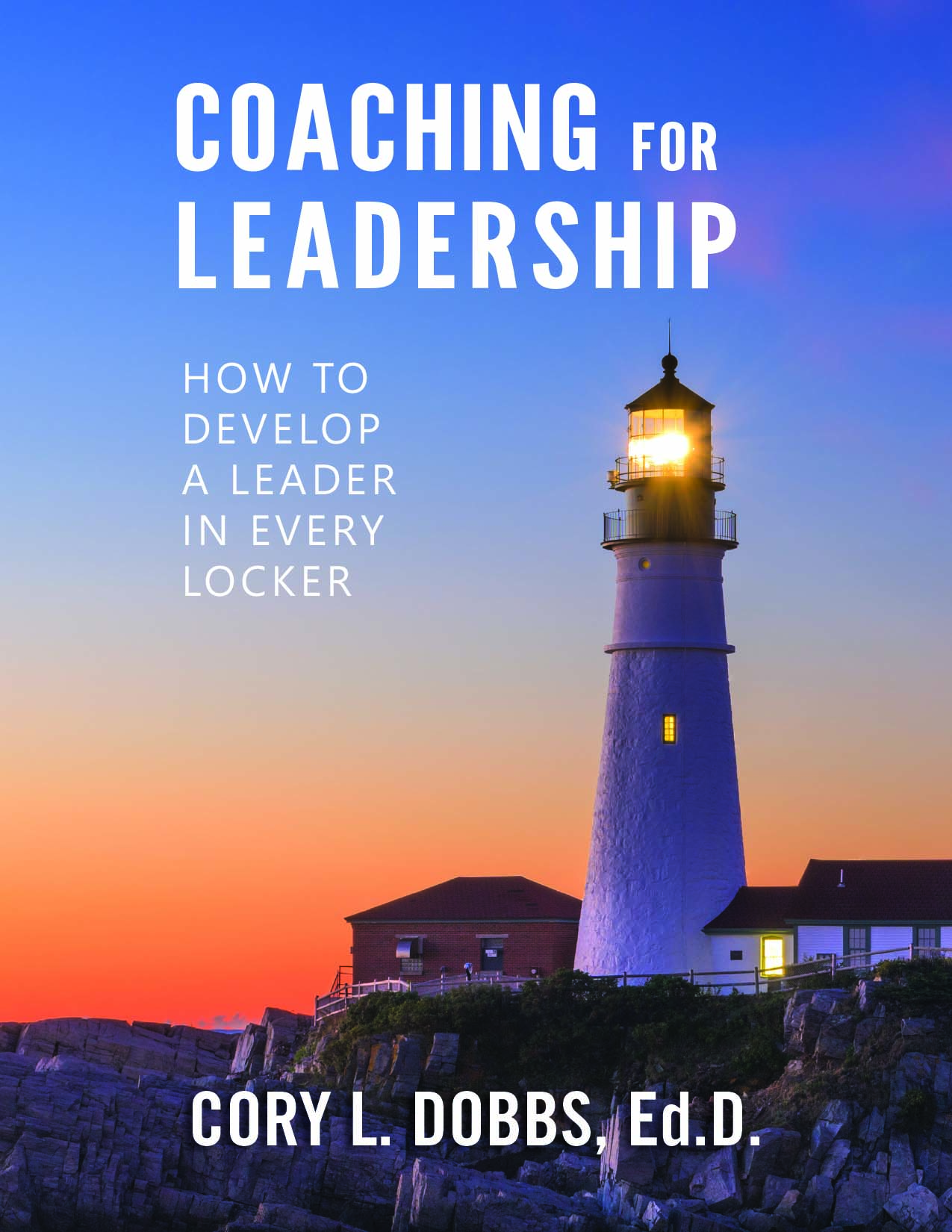

“Tell me and I’ll forget. Show me and I may remember. Involve me and I will care.” -Your Student-Athlete The world of coaching is changing. In Coaching for Leadership you’ll discover the foundations for designing, building, and sustaining a leadership focused culture for building a high-performance team. To find out more about and order Sport Leadership Books authored by Dr. Dobbs including Coaching for Leadership, click this link: The Academy for Sport Leadership Books